“On the eastern fringes of the city, Mughalpura had become inhabited when some of the captured Mongol soldiers were allowed to settle here outside the city”

Lahore has expanded in ways that were unimaginable even a mere quarter of a century ago. With no masterplan, its expansion has been haphazard and at the mercy of realtors. The civic body responsible for its development, the Lahore Development Authority (LDA), has mostly been a toothless organisation; operating under the unjust pressure of successive Punjab governments and with its employees susceptible to fall under illicit incentives – no different, it must be added, from other civic development authorities in Pakistan. The least that LDA and the Punjab government could do was to create a master plan, but that was not to be.

The origins of Lahore are shrouded in mystery and folklore. Hindu mythology records that Lohawar and Kusawar were sons of Rama, the hero of the Ramayana, with the former as the founder of Lahore and the latter that of Kasur. Knowing that the Aryan migrations to India occurred in about 1500 BC, this reference cannot be older than that. In some of the ancient writings, Lahore is mentioned not as a city but as a principality. In Puranas, the ancient religious-historical Sanskrit texts, a town in this part of the Punjab is known as Lavpur. In old Rajput chronicles, the town is referred to as Loh Kot, meaning the fort of Loh. This indicates that some important person by the name of Loh, whoever he was, initiated the settlement of Lahore.

In an attempt to fix a date for the establishment of the town, it is noteworthy that the very meticulous Greek writers accompanying Alexander during his invasion of India (326 BC) have not mentioned Lahore. Thereafter, another keen observer, Xuanzang, the Chinese traveler who toured this part of north India in circa 630 AD, mentions Sangla, Kasur (where he stayed for one month), Jullandhara, and Kannuj but not Lahore. Perhaps Lahore was an insignificant town, if it did exist at that time. However, some references, especially by the Egyptian Greek geographer Ptolemy (Batlimus in Arabic, who lived circa 150 AD), suggest that the city existed in 150 AD. Therefore, it can reliably be considered that Lahore was founded at the dawn of the Christian era.

Lahore As It Once Was: Minto Park Through The Ages

Lahore’s development since earliest times has been documented by, among others, SM Latif, Col Goulding, and Kanhaiya Lal Kapoor. It has been successively built, destroyed, and rebuilt a number of times. Kapoor has recorded thirteen instances of its destruction, including by Mahmud Ghaznavi, Shahabuddin Ghauri, Tajjudin Yalduz (twice by this Ghauri slave general), the Mongols (three times), the Ghakkars of Jammu, Ahmad Shah Abdali (Durrani), and the Sikhs. Unfortunately, there is no record of the location of the habitations that were destroyed by Ghaznavi. The city that we have now at its current location started its life in the 1020–1040 AD period, during the reign of Malik Ayaz.

Malik Ayaz, the favourite slave-soldier of Mahmud Ghazni, was appointed governor of Lahore in 1021. He built a mud fort, known as Kacha Kot, inside Lohari Gate, which served as the main entrance to this fort. Chowk Sootar Mandi (crossing of yarn market) constituted one important centre of Kacha Kot. The lay of the streets also suggests the boundaries of this fort. The area enclosed by the southern sections of Suter Mandi on the east, Said Mitha Bazaar on the west, Pir Bhola Gali in the north, and Lohari Mandi Bazaar on the south forms a higher ground than the surrounding areas, suggesting this to be an appropriate site for the fort. The historical Neeven Masjid (Low Mosque) at the Pappar Mandi Chowk, slightly outside this quadrangle, is about twenty feet below the street level, suggesting that it was built in a depression outside the fort. That depression was filled up over the centuries, leaving the mosque below street level.

In 1040 AD, Malik Ayaz died and was buried at what now forms the junction of Sarafa Bazaar (jeweller’s market) and Shah Alam Bazaars. For the reigning ruler to be buried here means that the place was either a graveyard or a park outside the then city. Eventually, the city expanded north and caught up with the river. After it was partially burnt and destroyed by Babur in 1525, it remained in a ruinous state for a few decades. By the time Emperor Akbar assumed the throne in 1555, it is reported in the book Haft Aqlim that Lahore was nothing more than a collection of a few hamlets from the Taxali-Bhaati Gate line to the Shah Alam Bazaar. The area to the east of the latter was an open field.

Pentagon’s 2024 Report: China’s Military Expansion Fuels Growing US-China Rivalry

The city remained more or less in the same state till the arrival of Emperor Akbar, for his 14-year-long stay here from 1585 to 1599. One of the first steps that Akbar took was to order the creation of housing area for the expanding population on the eastern side of Shah Alam Bazaar. This area developed in a ‘kidney shape’ whose alignment altered with the flow of the curving River Ravi. It included Mochi Gate in the south to Kashmiri Bazaar in the north and then right up to the then river alignment parallel to the Maulana Obaid Anwar road along the northern city wall. The names of streets and localities in this rather ‘planned’ area are meaningful and profession related. They include names such as Kucha Sadakaran, Kucha Kamangaran, Katra Purbian, Kucha Chabak Swaran, Kucha Killi Khana, Kucha Jrahan, Lakkar Mandi, Gali Dhobian, Gali Arayan, Gali Lath Maran, Kucha Baghicha Smadhi, Gur Mandi, Akbari Ghalla Mandi, Gali Darzian, Wehra Tailian, etc. This author had the pleasure of roaming through these streets yet again, about two months ago.

The wall around the city and its gates are the legacy of Emperor Akbar. Manucci (vol II, pp 185-6), who accompanied Emperor Aurangzeb to Lahore in 1673-74, mentions the names of eleven gates (he uses the term Darwazah). The names that he wrote are Qadri (on the river bank towards the north, initially also called Khizri and now known as Sheranwala Gate), Yakki (on the northeast corner), Dilli (on the route to Delhi), Akbari, Mochi (Manucci gives a story about the origin of this name), Shah Alami, Bhaati, Multani (on the road to Multan), Mori, Ghakkar (leading to the lands of the Ghakkars) and Kashmiri (on the road to Kashmir). Eight of these names are the same as used now. Multani and Ghakkar gates are no more, unless one of these was later renamed as Taxali Gate. Manucci doesn’t mention Lohari though it is known to be the first gate built as an entrance to the Kacha Kot. He mentions that there were twelve gates but names only eleven, thus he may have missed the name of Lohari Gate. Two gates, namely Raushanai and Masti, were developed later, when the Ravi moved away to the north, leaving the area below the northern walls of the Fort and the Mosque dry enough for commuters to traverse. During Mughal times, the city had a great reputation as the center of the Empire. John Milton wrote his epic poem ‘Paradise Lost’ in the 1660s where one of the lines reads as, ‘Agra and Lahore, the Seat of the Great Mughal.’ This line was written at the beginning of the half-century-long reign of Aurangzeb, when the British were still traders in India with no ambitions or illusions of becoming its masters.

Lahore As It Once Was: Jahangir’s Tomb Complex

On the eastern fringes of the city, Mughalpura had become inhabited when some of the captured Mongol soldiers were allowed to settle here outside the city. During the later Mughal era, the elite of the city moved to Mughalpura where they built large havelis. Zikria Khan and Shahnawaz Khan, the Mughal governors of Lahore in the mid-18th century, resided in this locality. Ahmad Shah Abdali plundered this area during his raids. Later, the Sikhs too looted the area for its remaining riches. Because of lack of security and frequent looting, Mughalpura became deserted. During the rule of the Sikh triumvirate between 1765 and 1799, this part of the city fell under the control of Gujjar Singh Bangi, who tried to resettle it by offering security and amenities. The general picture of Lahore, as witnessed by a British visitor in 1809 (Col. Goulding, Old Lahore) was of a city in decay and depopulated with crumbling buildings and the habitation confined to within the walls.

The city began to expand under the peace imposed by Ranjit Singh. Some elite residents developed farm houses with large gardens attached to them. On a map from 1839, the oldest map of Lahore that this author could find, there are seventeen gardens marked in north Lahore. During Ranjit Singh’s rule, the Mughal buildings in Mughalpura were ransacked for bricks and marble, to be used in the new buildings constructed for Sikh elites. The arms factories at Mughalpura, where Abdali had his guns manufactured, were reactivated. A cantonment was developed a little north of Mian Mir’s tomb for cavalry. By the end of the Sikh rule of about fifty years, the city had expanded to the south and the east to a circumference of about 25 kilometres over an area of 25 sq km.

Lahore As It Once Was: Rise Of The Cantonment

The British captured Lahore in 1845 and ruled the city for a century. It is fashionable to label the colonial administrators as mere looters and plunderers but they were also world conquerors with grand development visions. They first built a well-planned cantonment on a grand scale across the canal in the east, and a wide complex of civil and judicial administration on the west end of the city adjacent to the walled city. Then they linked the two with a wide road, the Mall Road; perhaps the widest that they had so far built in their Indian empire and only to be exceeded in magnificence by Kingsway in New Delhi in 1916. Originally, the Mall Road was called Lawrence Road but over time, it came to be known by its current name.

One of the first steps that Emperor Akbar took was to order the creation of housing area for the expanding population on the eastern side of Shah Alam Bazaar

The British and the Anglicised local elite developed new localities like Gowalmandi for the middle class, Krishan Nagar for upper middle class and Model Town for the rich business and professional community. They built great parks like the Lawrence Garden, Race Course ground and the Gymkhana. Unlike the gardens developed by the Mughals, these parks were open to the public and not reserved only for the royals. Large educational and medical institutions such as the Government College, the Aitchison, FC College, Mayo Hospital, King Edward Medical College, Punjab University, Engineering College, Railway Technical School, Mayo Arts College, the Veterinary education college, Gulab Devi TB hospital, De Montmorency Dental College, Lady Wellington hospital, Lady Aitchison Hospital for women, and many more such institutions were established, or inspired, by the British. Many middle level educational institutions like Mission High School, Central Model, Muslim Model, Islamia College, and a string of primary schools were also developed. They created efficient hubs of transportation like the great fortified railway station outside Delhi Gate and a road transport hub at Badami Bagh outside Masti Gate. Modern facilities like Lunatic asylum and Jails were also established. It was the first era in the history of the subcontinent that the government had taken interest in creating institutions of public interest and benefit. Lahore moved from its medieval living into the modern world under the British tutelage. These developments, in a little under hundred years of colonial rule, expanded the city to a circumference of 50 kilometres with an area of about 110 sq km.

Lahore As It Once Was: The History Of Old And Present-Day Ravi

The contributions of the local engineers and contractors also need to be acknowledged here. They were Kanhaiya Lal Kapoor, an engineer in the newly established PWD under the British rule, Bhai Ram Singh, an architect in PWD and the contractor-builder Sir Ganga Ram. Modern Lahore is a reflection of their vision and dedication.

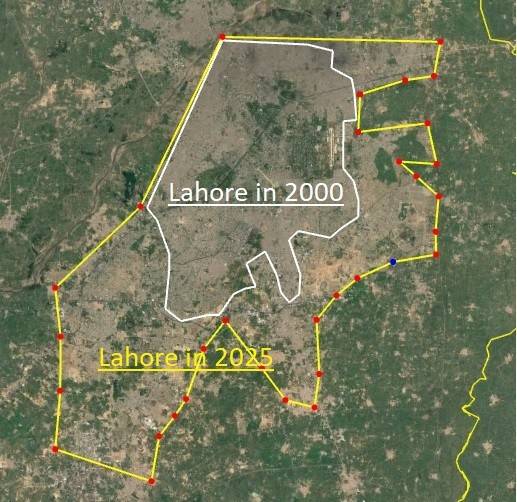

A comparison of circumferences and areas of Lahore in various eras gives an idea about the scale of its expansion. The original walled city, which is the actual Lahore with its ancient bylanes, winding streets, historic monuments, is only a little over six kilometres in circumference and, according to SM Latif (ibid) 461 acres or 2.5 sq km in area. Emperor Shah Jahan added Shalimar Gardens and the attached locality of Baghbanpura but they were isolated places well to the east of the city along the road to Amritsar and Delhi. Thornton, a British civil servant estimates that during the time of Shah Jahan, the city suburbs may have extended east to about 15 sq km. Thereafter, the city greatly reduced in population and size due to civil disturbances that lasted till Ranjit Singh united Punjab. Under his rule, the city again expanded to a little over 23 sq km. The British expanded the city by four times in their nearly hundred years of occupation to 108 sq km. Post-independence, the city has multiplied by ten times in three quarters of a century and there is no end in sight. There has been a rapid expansion with emergence of multiple housing societies, especially in the south. The city had a diameter of 85 km at the turn of this century that has increased in a quarter of century to 145 km, while the area has spread from about 350 sq km to over 800 sq km. Unfortunately, this expansion has come about without any metropolitan master plan. Individual societies have their own town planning but an RDA master plan is lacking.

Lahore As It Once Was: Bridging The Ravi

Comparative figures for population offer a very interesting read. Though accurate records for Mughal era are not available, yet it is estimated that by the end of Aurangzeb rule, the city and its suburbs had a population of four hundred thousand. Thereafter, due to breakdown of law and order, Abdali’s raids and Sikh internecine disturbances, the population, especially in the suburbs, reduced and was recorded by the British as a hundred and thirty thousand in 1875. By independence, the city had a healthy population of about 700,000, which has now increased to fourteen million; a twenty fold growth in seventy five years which is 2% per annum. At this rate, the city will add a million people to its cramped streets every three years.

The northern and north-eastern portions of the city were a favourite location for gardens during the Mughal as well as the Sikh eras. The oldest surviving structure here is the Hujra of Mir Mahdi, believed to have been built in early 1400s after the Ghakkar rulers of Jammu had destroyed the city and killed its inhabitants. One of the earliest surviving – though barely – Mughal monuments here in Kot Khawaja Saeed, is a tomb commonly but erroneously referred to as that of Prince Pervez, a son of Emperor Jahangir. It was constructed in a garden that the Prince created here and, as the prince is buried in Agra, this may be the burial place of two of his sons who were murdered by Asaf Khan on the orders of Shah Jahan on assuming power. This portion of the city is densely populated and is separated from the main city in the south by the Amritsar-Shahdara railway line. The distance between the railway bridge over the Ravi and Pak-India border along the railway line is thirty kilometres, and except for a small portion towards the border, this entire length up and down is now heavily populated.

Lahore: Eternal City Of Life, Legacy And Longing

Expansion of Lahore under the Ravi Urban Development Authority (RUDA), along the Ravi from Shahdara Reserve Forest north of Ring Road to near Sharaqpur, will add another dimension to the city. It encompasses about a hundred thousand acres and will add state-of-the-art modern housing areas with vast economic activity. On the eastern side, the city is already touching the BRB canal, beyond which its expansion is limited by the Indo-Pak border.

Although the city has expanded beyond recognition and mostly without a master plan, the name Lahore, for this author and for old Lahoris, defines only its walled portion, and the area enclosed by the Mall on the south, the Canal on the east and the Ravi on the west. All areas beyond were villages around Lahore that are an addition to the city due to rapid growth of population. The areas beyond, especially the ones across the canal, are a different world with no semblance of Lahori culture or character. They need to be given other names. The same applies to some of the other large towns of Pakistan. In case of Islamabad, the people living near Nelson’s Column on GT Road in northwest of Rawalpindi, near Fateh Jang on Kohat Road, along the motorway near Islamabad interchange and in the vicinity of Rawat, also write Islamabad as their city. DHA phase-1 is Rawalpindi but has assumed the name of Islamabad, as no locality beyond Morgah or Ayub National Park wants to be labelled as Rawalpindi. In case of Karachi, people living closer to Hyderabad too claim the former rather than the later as the city of their residence. Peshawar has gobbled up the historic villages of Jhagra, Chamkani and Jamrud. This is ridiculous. Some sense should be inculcated in the naming scheme of cities.

Lahore has now become the leading cultural centre of Pakistan. It has a rich literary, culinary, industrial and political significance with influence over other parts of the country. Greater Lahore is ethnically very diverse as against the Walled City, which is homogeneous and old-style Lahori. The city is slated to expand further and hopefully to greater glories.

Reference Link:- https://thefridaytimes.com/31-Mar-2025/lahore-as-it-once-was-expansion-of-the-city-through-the-ages