This escalating crisis unfolds despite significant governmental pushes towards technological solutions, suggesting that tech interventions alone are insufficient to stem the tide without addressing deep-seated structural issues.

India’s judicial system is buckling under an unprecedented weight, with the total number of pending cases across high courts and subordinate courts surging past the five crore mark by the end of 2024, reveals the latest India Justice Report (IJR) 2025.

This staggering figure is not just a static snapshot; it represents a worrying trend, with the report noting a significant increase of over 30% in the backlog across all court levels since 2020. The justice delivery system is demonstrably struggling to keep pace, let alone reduce the existing mountain of cases.

This escalating crisis unfolds despite significant governmental pushes towards technological solutions like e-filing and digitisation, suggesting that tech interventions alone are insufficient to stem the tide without addressing deep-seated structural issues. The human cost is immense, translating into justice delayed by years, potentially eroding public faith and directly fuelling the overcrowding crisis in the nation’s prisons.

Figure 13: Cases pending in high courts

The true measure of the delay lies in the age of pending cases. Nationally, more than half (51%) of all cases awaiting resolution in high courts have been languishing for over five years (Fig 13). High courts like Allahabad and Punjab & Haryana report over 60% of their cases falling into this aged category.

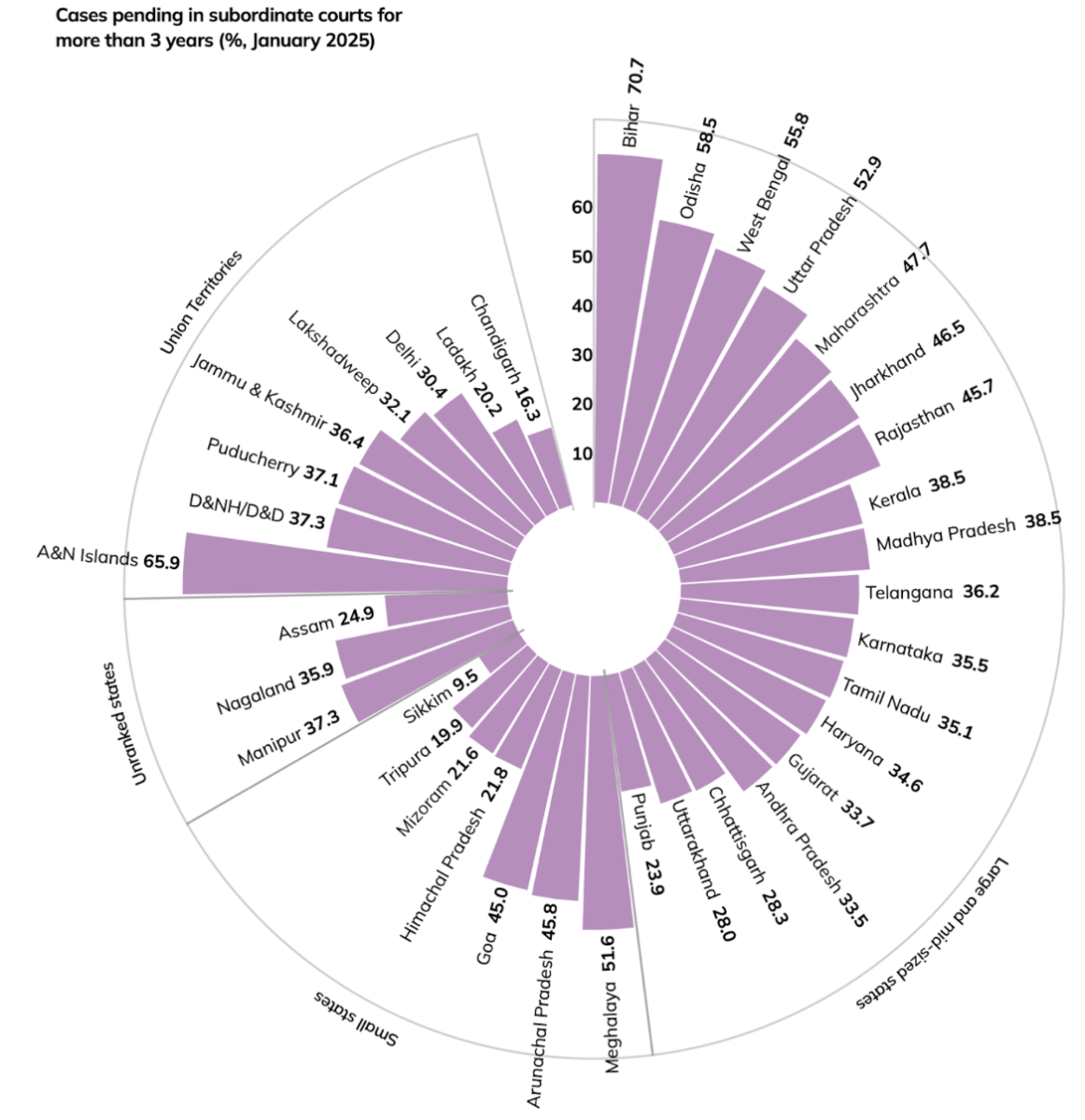

Figure 12: Cases pending for more than 3 years in subordinate courts

The situation is mirrored, albeit less severely, in the subordinate courts – the first point of contact for most citizens. In 22 of the 25 ranked states, over 25% of subordinate court cases have been pending for more than three years. The situation is particularly dire in states like Bihar (a staggering 71%), and West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and Odisha (Fig 12), where over 45% of cases have languished for more than three years.

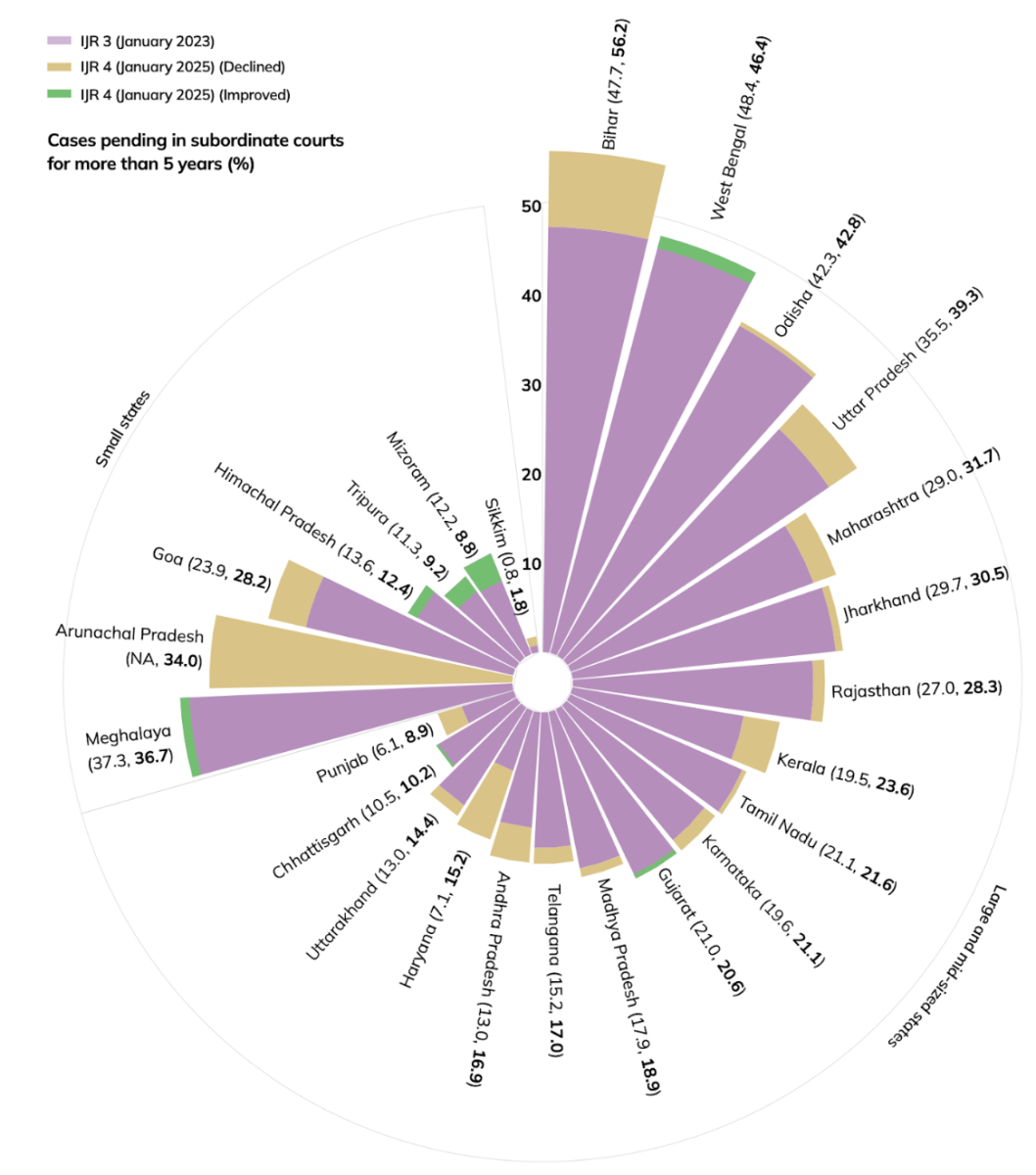

Figure 14: Cases pending for more than 5 years in subordinate courts

In 10 states, over 25% of subordinate court cases are pending for more than five years (Fig 14). For countless litigants, navigating the halls of justice has become a multi-year, often decade-long, ordeal.

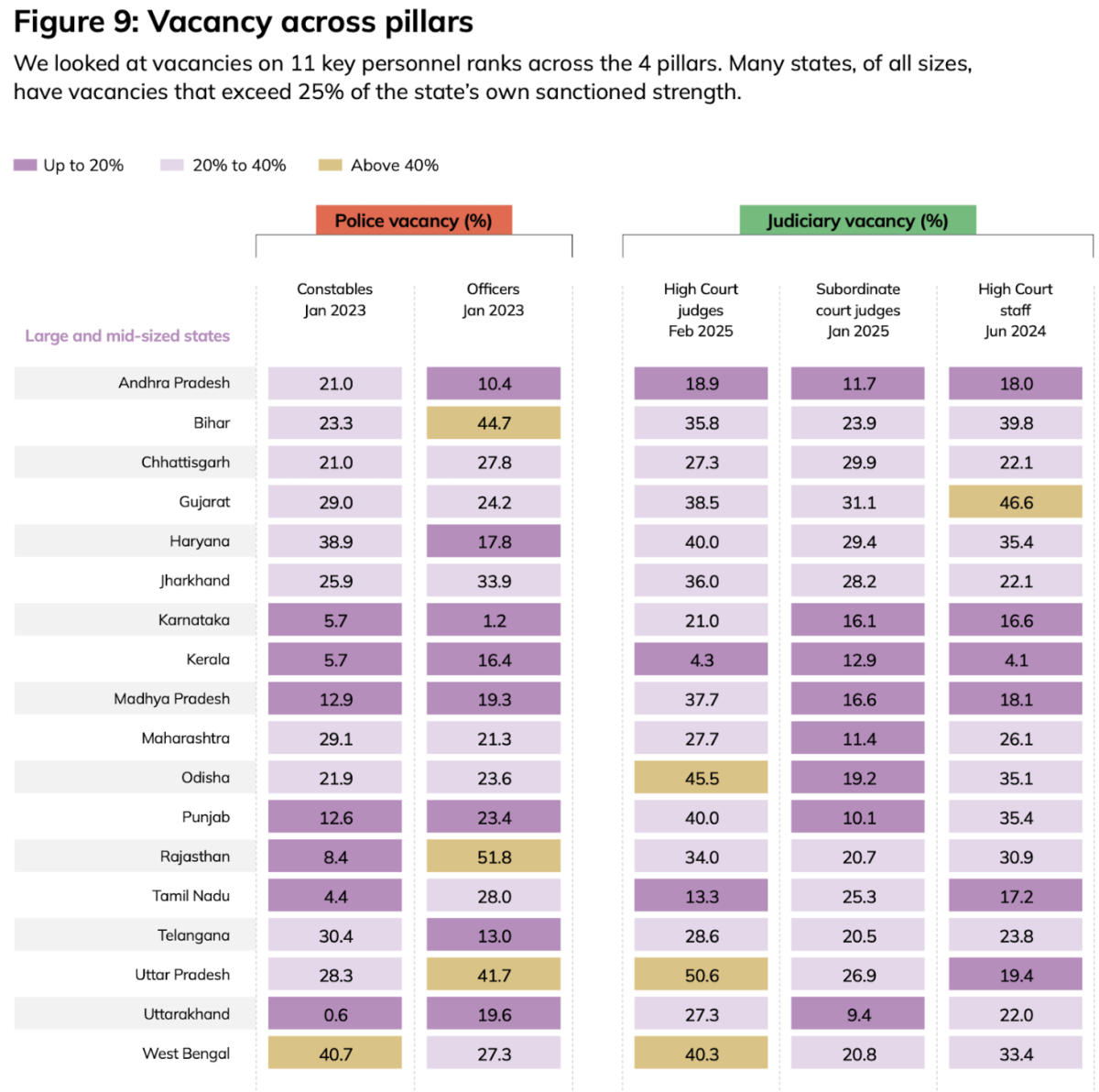

A primary driver pinpointed by the report remains the persistent and chronic shortage of judges. Nationally, vacancies continue to hover around 21% in the subordinate courts and a critical 33% in high courts (Fig 9). This shortage persists despite efforts, including record high court judge appointments in 2022 which, the report notes, barely dented the overall vacancy percentage.

This means roughly one in three high court positions and one in five subordinate court positions remain unfilled, creating an unsustainable pressure on the serving judges and inevitably slowing down the pace of justice.

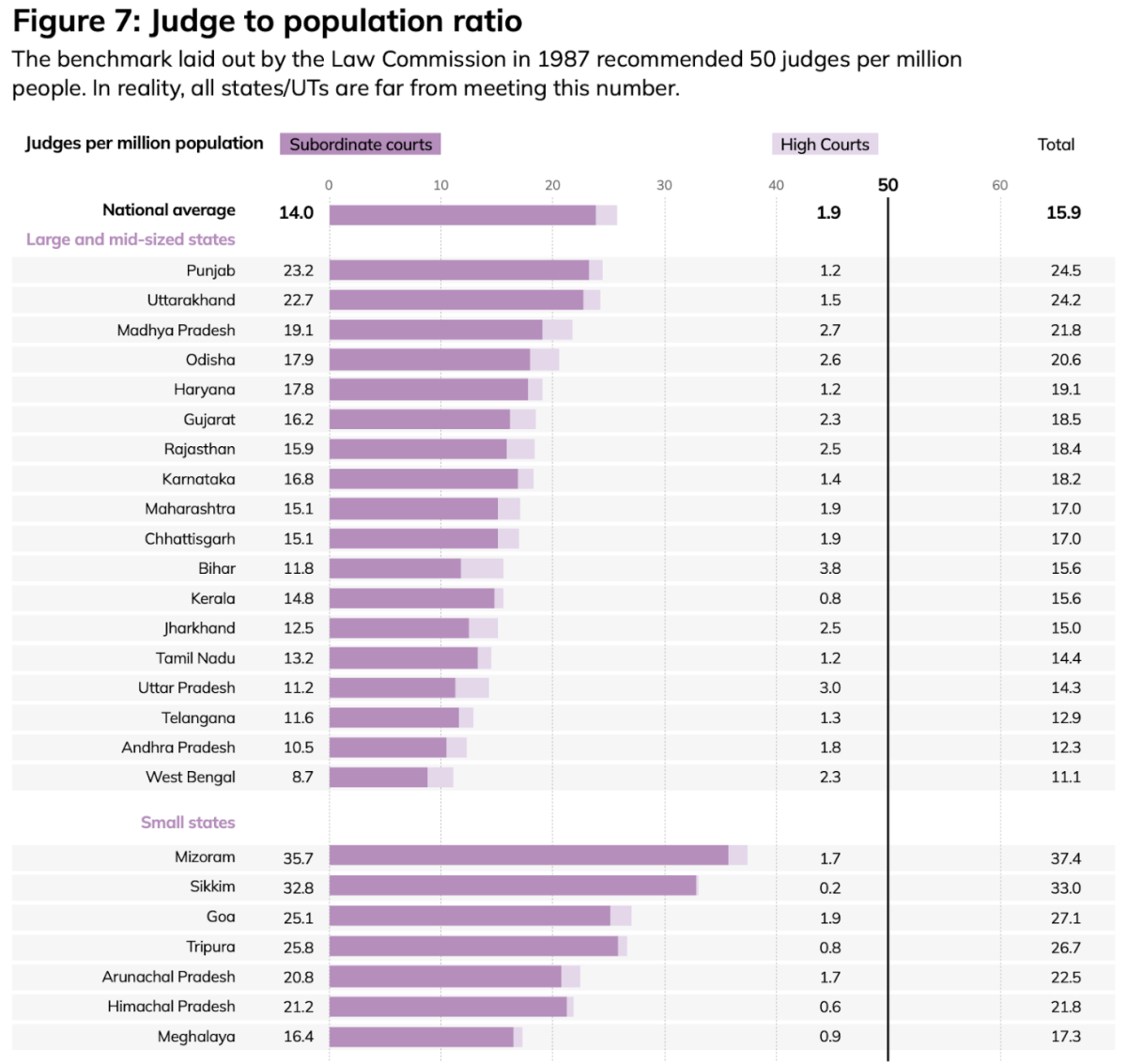

Compounding the vacancy issue is the fundamentally inadequate number of judges relative to India’s vast population. The country averages only 15 sitting judges (across HCs and subordinate courts) per million people (Fig 7). This figure stands in stark contrast to the 50 judges per million recommended by the law commission as far back as 1987.

While states like Sikkim (33 judges per million) fare better, populous states like Bihar, West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh function with around 10 judges per million or fewer, highlighting the immense capacity gap.

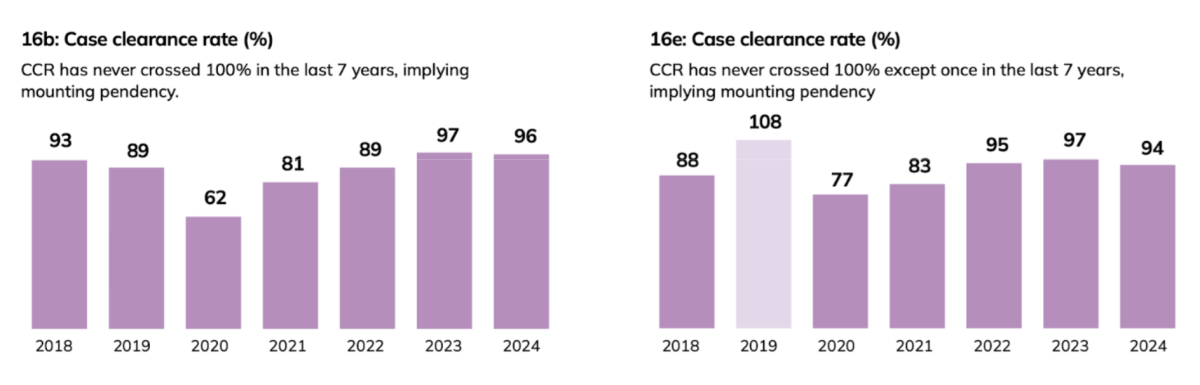

Figure 16b: Subordinate courts; 16e: high courts

The Case Clearance Rate (CCR) – the court’s ability to dispose of cases relative to those filed in a year – offers further cause for concern, particularly at the higher judicial level. While subordinate courts nationally managed a CCR of 96%, high courts averaged just 94% in 2024 (Fig 16). A rate below 100% means the backlog is actively growing. Worryingly, this marks a slight deterioration for high courts compared to previous years, and crucial courts like Bombay, Delhi and Gujarat have consistently struggled to cross this threshold in recent years.

The persistence of these issues, despite the national push towards e-courts, virtual hearings, and the NJDG data portal, highlights a critical point: technology is a tool, not a panacea. Without addressing the fundamental shortages in judges and potentially support staff and streamlining processes, technology’s impact remains limited.

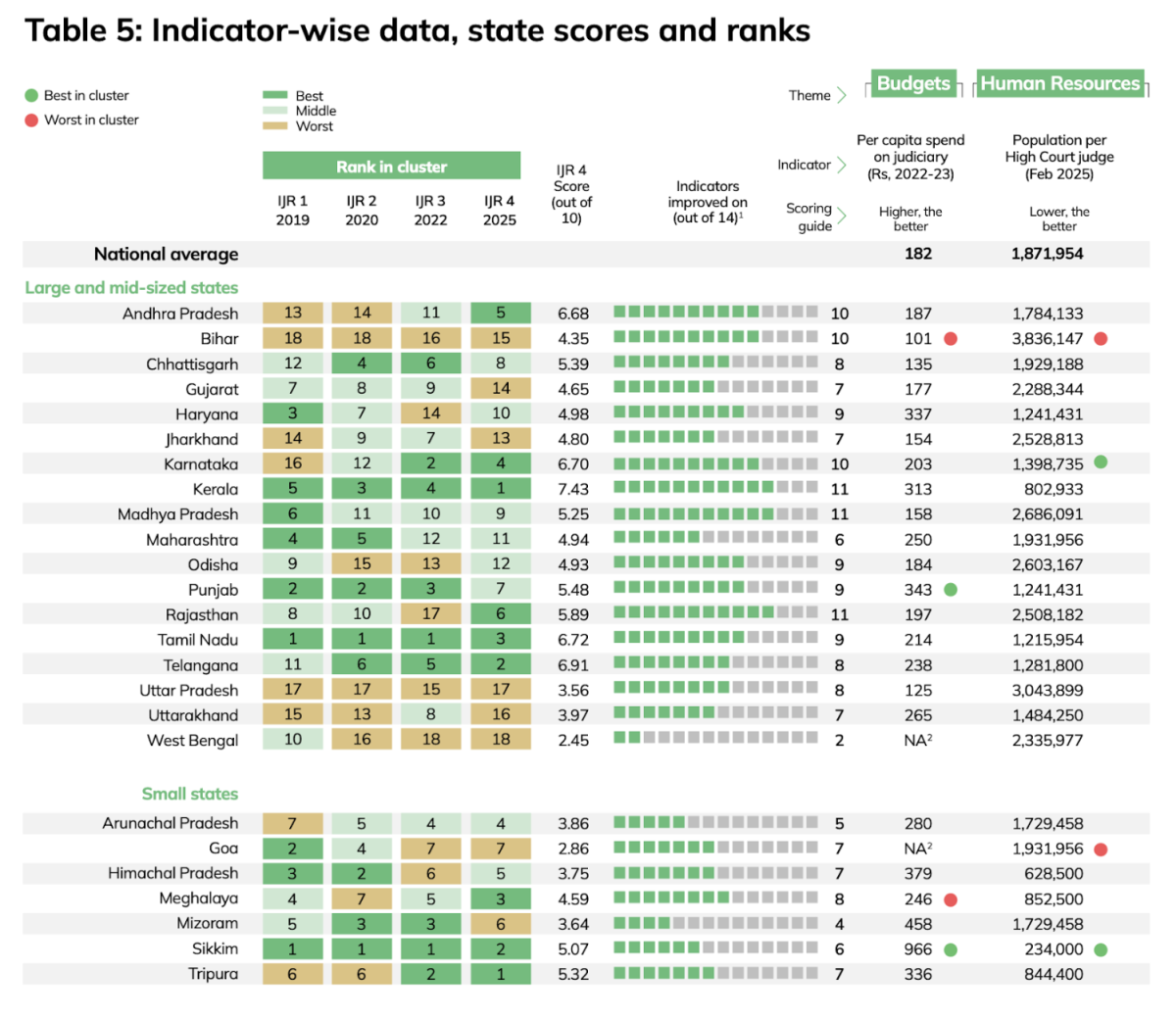

The report also touches upon resource constraints, noting low per capita judicial spending in several high-pendency states like Bihar (Rs 101) and Uttar Pradesh (Rs 125) (Table 5), and the fact that salaries consume the bulk of budgets, possibly leaving insufficient funds for vital infrastructure and process improvements.

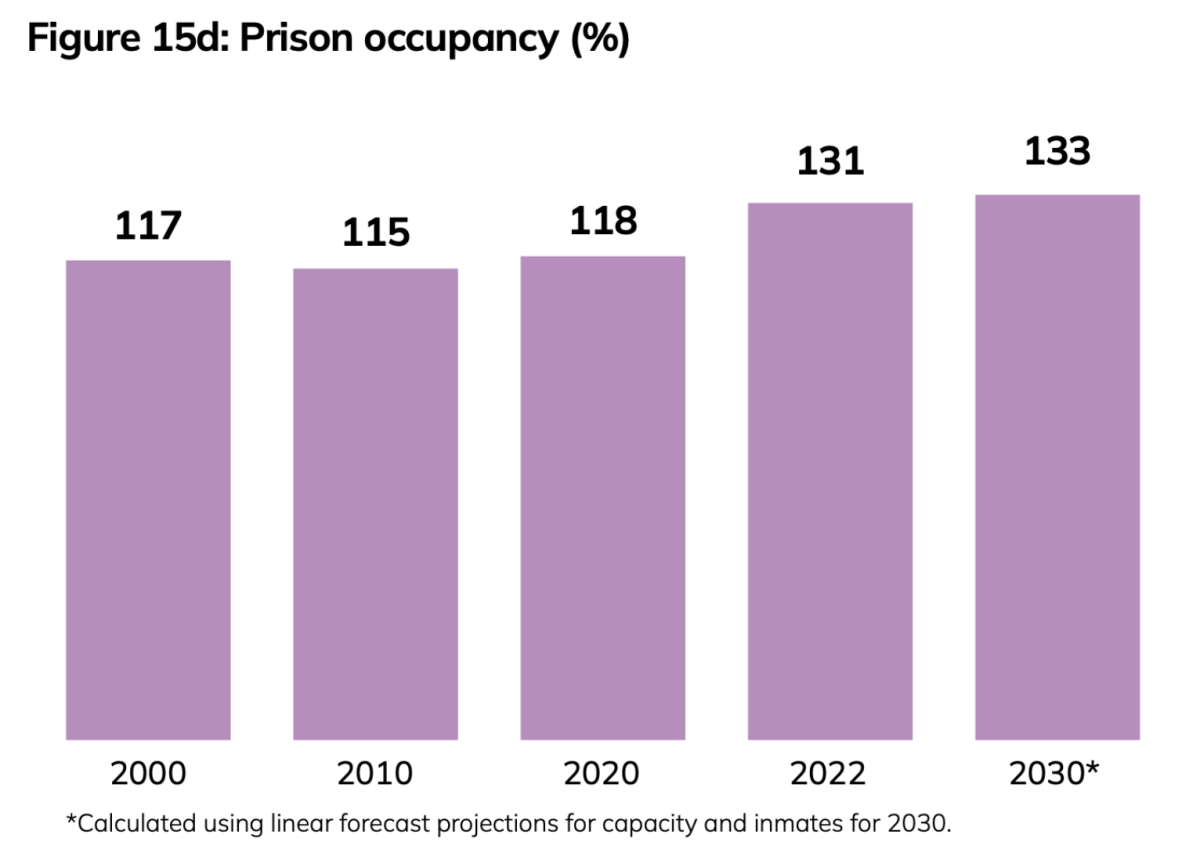

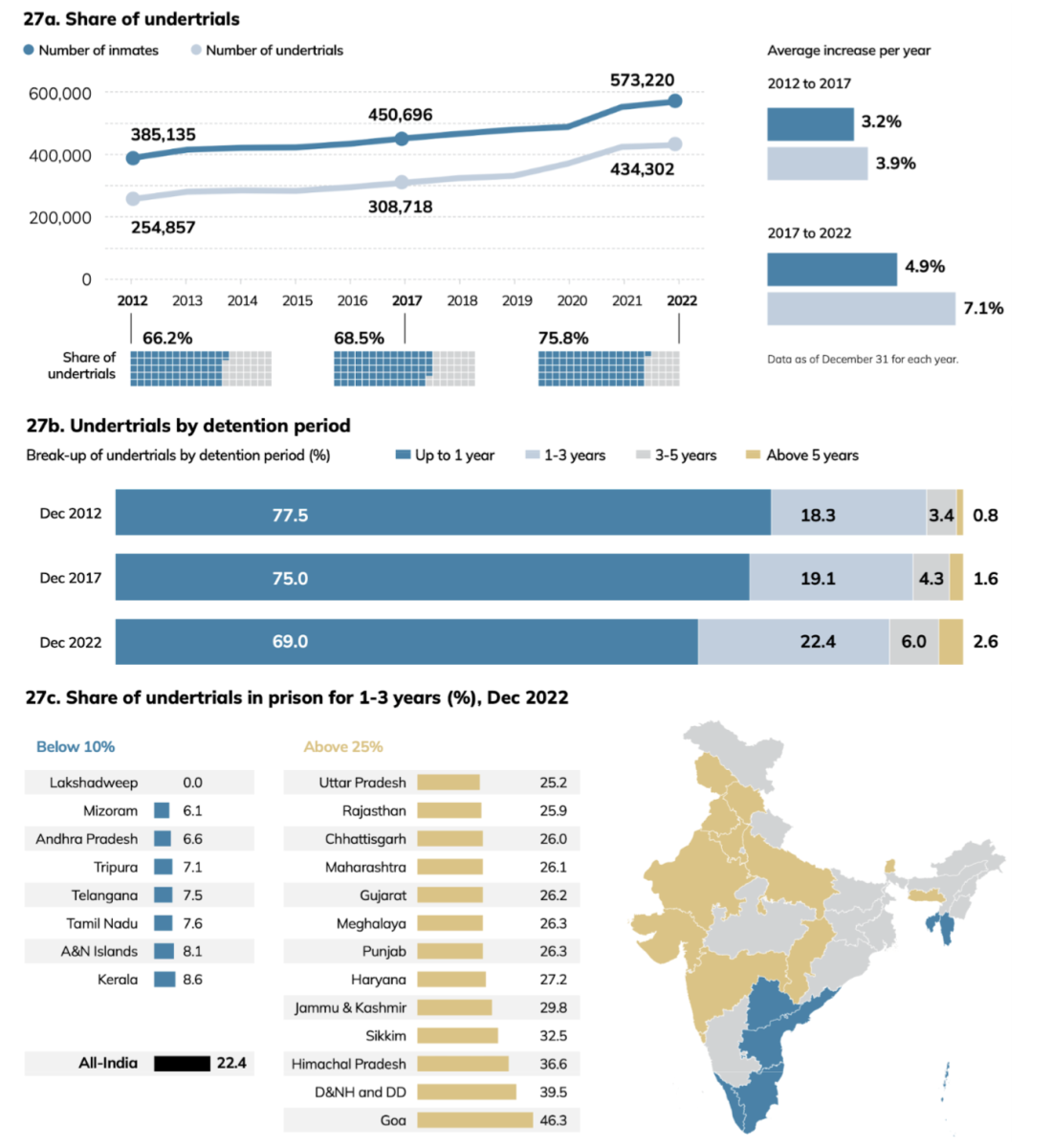

The consequences of the judicial logjam spill directly into India’s overcrowded prisons. The report starkly links the court backlog to the alarming fact that 76% of India’s 5.7 lakh prison population comprises undertrials (Fig 15d) – individuals awaiting the conclusion of their investigation or trial.

Furthermore, Figure 27 shows undertrials are spending longer behind bars; 22% spent 1-3 years incarcerated in 2022. Delayed trials mean prolonged pre-trial detention, directly contributing to the prison crisis.

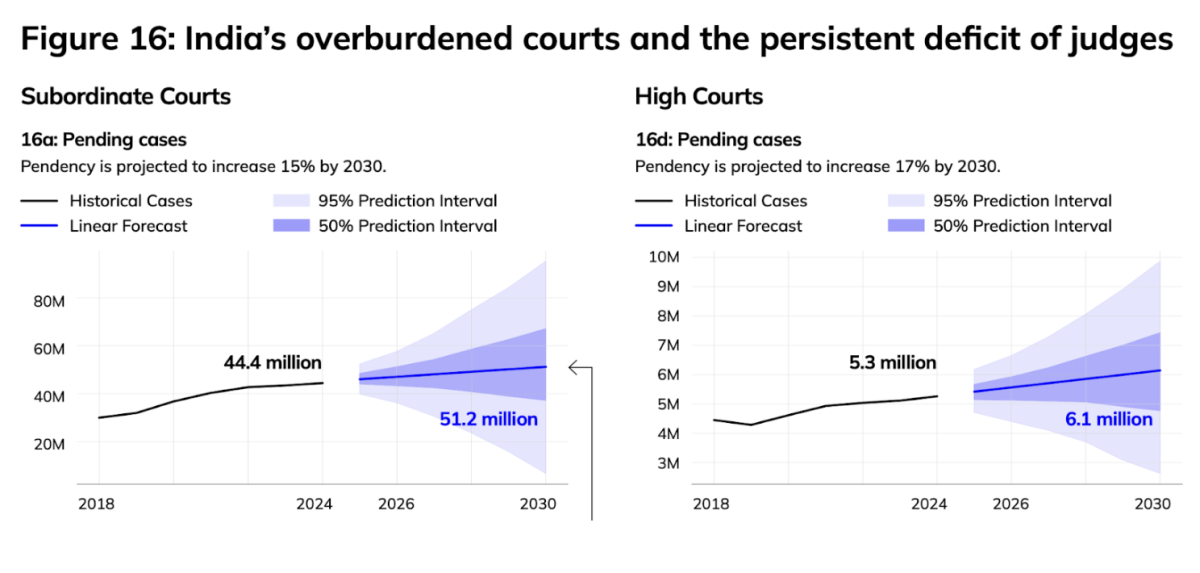

If current trends continue, the situation is projected to worsen. Based on its analysis, the report forecasts that by 2030, subordinate court pendency could swell towards 5.12 crore, while high court pendency could approach 61 lakh (Fig 16a/d).

Reference Link:- https://thewire.in/law/5-crore-cases-and-counting-indias-courts-are-struggling-to-clear-the-pile-up